1.“I count the grains of sand on the beach and measure the sea; I understand the speech of the dumb and hear the voiceless.”

The Pythia

- “Tell the king, the fair-wrought house has fallen. No shelter has Apollo, nor sacred laurel leaves; The fountains now are silent; the voice is stilled.”

Pythia’s last oracular reply

![John Collier,]()

John Collier, “Priestess of Delphi”

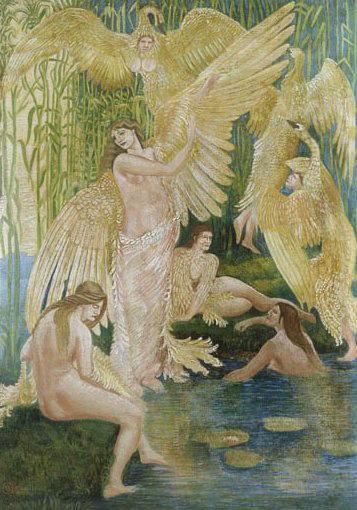

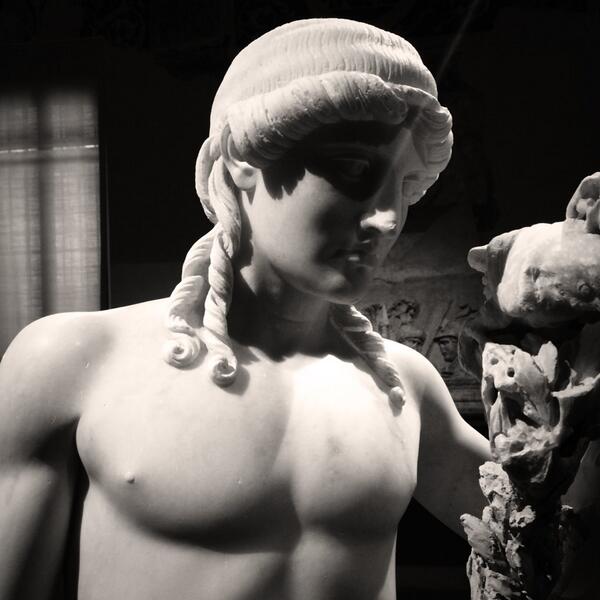

In an extraordinary poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” Reiner Maria Rilke is faced with the ultimate mystery of divinity. A torso of the Greek sun god reveals to him his own inner God image – that elusive, transcendent centre of the psyche, which, like the mysterious centre of a mandala, or our inner galactic rotational centre, attracts, magnetizes and organizes all of our psychological processes. Jung called it the Self. The last line of the poem – “You must change your life” – echoes the famous inscription “Know Thyself” from the Apollonian oracle in Delphi. To know oneself means to accept the supremacy of the Self, that mysterious mover and shaker that brings about what we call Fate for lack of a better word. This process must and will result in a transformation. I am quoting the poem in Edward Snow’s translation:

“We never knew his head and all the light

that ripened in his fabled eyes. But

his torso still glows like a gas lamp dimmed

in which his gaze, lit long ago,

holds fast and shines. Otherwise the surge of the breast

could not blind you, nor a smile

run through the slight twist of the loins

toward that center where procreation thrived.

Otherwise this stone would stand deformed and curt

under the shoulders’ transparent plunge

and not glisten just like wild beasts’ fur

and not burst forth from all its contours

like a star: for there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.”

On of Apollo’s epithets was Phoebus, which meant pure or holy. He presided over most of Greek renowned oracular shrines, where multitudes flocked to reconnect with their own inner pure and holy place, and thus find answers to questions of various magnitude. His was Didyma, Delphi and Clarus, while only Dodona belonged to Zeus, whose priestesses called Sybils interpreted the rustling of oak leaves. Porphyry thus described the three methods of divination used by three main Apollonian oracles:

“There are those who give oracles having drunk water, such as the priest of Clarian Apollo in Colophon; others are sitting over openings in the ground, such as the women who give oracles in Delphi; others again are breathing inspiration from water, such as the prophetesses in Didyma.”

Delphi was by far the greatest and most renowned. It marked the centre of the Greek inhabited world. As Roger Sworder explains:

“Inside the temple of Apollo at Delphi was a certain stone, the navel stone or omphalos, …. The story went that two eagles or swans flying in opposite directions from the furthest parts of the earth had met in Delphi at this stone. … The navel stone was hemispherical and sacred to the goddess Earth. …

The stone was inside the temple of Apollo. Also inside the temple was the oracular shrine of the Pythian prophetess. As in a womb, delphys, male and female, waking and sleeping, light and night were joined here. What was done here enacted the hidden point of the cosmic genesis and organized the ancient Greek world after its pattern. The omphalos showed that this was where the womb was. …

It was called the navel stone because it marked the representation of the cosmic womb. In this place the heart of space, the heart of thought and the heart of generation were at one. It is usual for oracular shrines to be placed at geographic centres. In the Vedas it is said that all oracles are set as is the nave within the wheel. A word for an oracular pronouncement in Greek is omphe, which is connected with omphalos. From here the Greek world opened out, guided by the principal thought at its center.”

![The Omphalos]()

The Omphalos

He continues:

“Delphi was the location of Mount Parnassus, a favorite place of Apollo and the Muses.

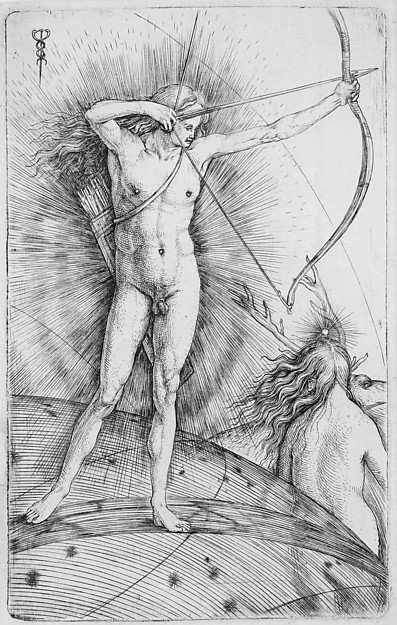

… The early Hymn to Pythian Apollo describes how the god came to Krisa, a foothill facing west beneath snowy Parnassus, and there decided to site his temple. Then he laid out all the foundations, wide and very long. The longer sides of the building were aligned east and west; the shorter sides, in one of which was the main entrance, north and south. … Guided by Justice Apollo surveyed the earth from his chariot, going from west to east in his yearly journey round the zodiac. In his temple he was the geographer of the Greeks. His laying out of its foundations symbolizes his nature. The lines he drew on the surfaces of earth and heaven ran straight as the arrows he shot from his bow. With this bow he killed Tityus and also the dragon from whose decay Delphi was called Pytho. These were victories of the mind which measures rather than of the reason which overcomes passion. He is pictured on many vases seated on the omphalos inside the temple, his bow and quiver hanging from a peg. The omphalos is covered with a net or knotted ropes, other symbols of geodesy.”

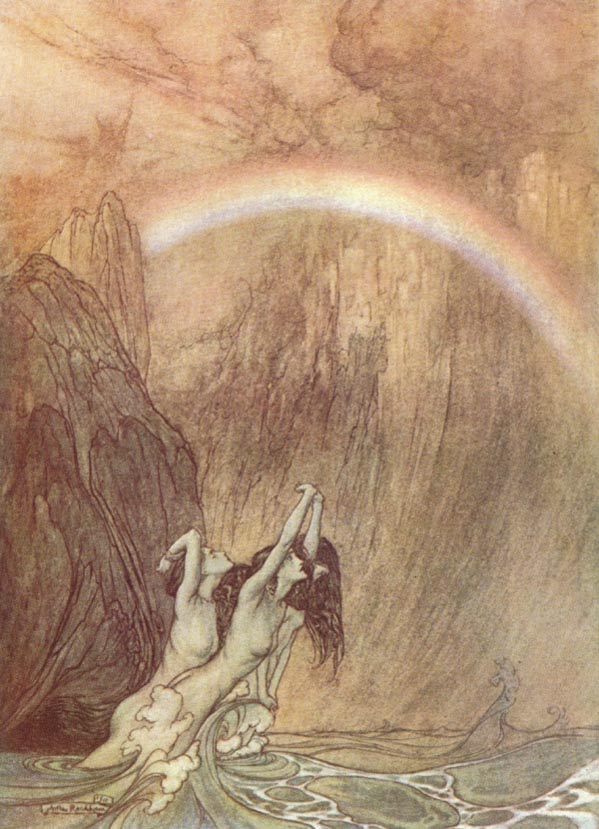

![J.M.W. Turner,]()

J.M.W. Turner, “Apollo and Python”

Similarly, Fritz Graf calls the establishment of the oracle at Delphi “a mythical feat that has cosmic dimensions, marking the beginning of the world as we know it.” According to the Homeric hymn to Apollo, the god killed a serpent/dragon and proceeded to call the place Pytho (Stinkton) after the stench of the rotting beast. We can also choose to read the story as one of an aggressive male God taking over the place, which long before him was sacred to earth goddess (with the snake as one of her attributes) and famous for its oracular properties. However, one simple fact seems to disprove that version, at least in my eyes: The Pythia, the high priestess of Delphi, was the highest spiritual authority and the only channel of divine will. She was the true and only messenger of the gods. Oracles revered the powers of the earth, its sacred springs and lofty rock formations. That was perhaps not a conquest but a loving assimilation, showing deeper understanding of the nature of divine inspiration.

![A vase depicting Apollo on a winged tripod over the sea with dolphins]()

A vase depicting Apollo on a winged tripod over the sea with dolphins

Before Apollo, the presiding deity in Delphi was Gaia, the earth goddess. In a scientific (and yet deeply spiritual) book on Delphi’s secrets, which was a true revelation for me, William J. Broad describes how from a geological perspective, with its mountains, canyons and cliffs, this is an absolutely unique, one-of-a-kind place in the world, “a place where primal forces have thrown open the secrets of the earth to human inquiry.” Behind the temple, the view was dominated by twin limestone cliffs called the Phaedriades (the Bright Ones or the Shining Rocks), which put on a golden hue as the sun rose and set. The cleft that nested the sanctuary was indeed like the womb, naturally flanked by imposing mountains on three sides. The place abounded in crystalline clear springs, which were believed by the locals to possess magical qualities. All this made Delphi a secluded retreat and a stunning sanctuary. Pilgrims must have been dazzled by an awesome display of Oracle’s wealth. A wide road lead through a row of impressive statues donated to Delphi by grateful rulers of ancient cities, past imposing buildings, up to the monumental Doric temple. The peak of Mount Parnassus, home of the Muses, a mountain sacred to both Apollo and Dionysus, towered over the sanctuary. Broad writes:

“First-time visitors surely gazed about in reverential silence. Some probably wept. Scores of statues of Apollo greeted pilgrims, one looking down from a height of nearly sixty feet. Made of bronze, it could gleam in the clear mountain air, not unlike the god of the sun himself.

The temple itself was a Doric gem. A bit smaller than the Parthenon, it arose in the fourth century BCE during Greece’s classical age and represented the culminating edifice of a series of temples that were increasingly large and stately. Its entrance bore such inscriptions as ‘Know Thyself’ and ‘Avoid Extremes’ lest visitors doubt their arrival at the epicenter of wisdom.”

![]()

Bronze head of Apollo from the Temple of Apollo in Pompeii

The importance and centrality of the Oracle in the culture of Ancient Greece cannot be overestimated, Broad emphasizes:

“No seer or diviner stood higher. No voice, civil or religious, carried further. No authority was more sought after or more influential. None. She quite literally had the power to depose kings. …

The evidence suggests that her words repeatedly changed the course of history. Over a vast period—ages in which peoples came and went, empires rose and fell—the Oracle proved to be the most durable and compelling force in what was arguably the most important society that humans ever devised. She was the guide star of Greek civilization. We have no equivalent. No religious or secular figure, no pope or imam, no celebrity or scientist, commands the kind of respect that the Greeks accorded the Oracle of Delphi. Her sacred precinct on the flanks of Mount Parnassus was the spiritual heart of the Hellenic world.”

A French archaeologist was quoted to say that the place was “full of mystery, grandeur and divine terror.” He was referring to his team unearthing the adyton – the sacred chamber positioned in the temple, where Pythia delivered her prophecies. She prophesized sitting on a tripod inside the adyton, which in ancient Greek means “do not enter.” She inhaled mysterious vapors rising from a cleft beneath her feet and enveloping her in a supernatural mist. Before a consultation, the Pythia would bathe herself in the waters of the Castalia spring. Priests would purify themselves in its waters, too. Next, they would all proceed to yet another holy spring – the Kassotis, which emerged from within the sanctuary itself. There the Pythia would drink its sacred waters. Finally, the Oracle would descend to the adyton, where she would sit on a tripod with the view of the omphalos flanked by two golden eagles of Zeus. Other sacred objects included a statue of Apollo and Grave of Dionysus. Her spiritual union with the god aided by her inhaling of sacred pneuma ensued. Broad summarizes: “The Pythia, presiding over the adyton, rapturous in her divine intoxication, would turn inward, reflect on the question, shake a laurel branch as the spirit of Apollo swept through her, and utter the god’s response. As the Pythia spoke, the priest recorded her words.”

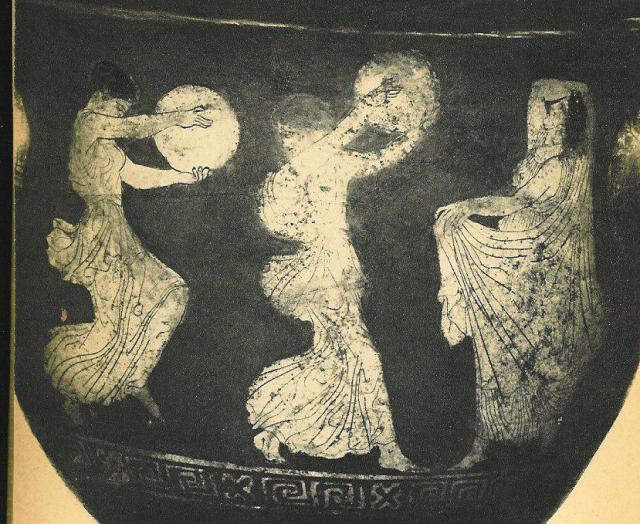

![“Around 440 BCE, an Athenian potter decorated a large cup with a portrait of the Delphic Oracle in the midst of a prophetic session. It turns out to be the only surviving image that we have of the Pythia from her own day. The illustration shows neither a rustic maid nor a youthful seductress. Rather, it portrays a woman in her prime, with full breasts and supple gracefulness, her long alb coming down to her ankles. She sits on the tripod, her bare feet dangling off the floor, her body slumped, not quite herself, thoughtful, her eyes gazing down, looking into a small dish, presumably filled with water from a sacred spring, perhaps fragrant with a sweet aroma. In her right hand she holds a sprig of laurel, Apollo’s holy plant. The ceiling of her oracular chamber is low, and beneath her feet, below the floor, the artist has depicted a void.” William J. Broad]()

“Around 440 BCE, an Athenian potter decorated a large cup with a portrait of the Delphic Oracle in the midst of a prophetic session. It turns out to be the only surviving image that we have of the Pythia from her own day. The illustration shows neither a rustic maid nor a youthful seductress. Rather, it portrays a woman in her prime, with full breasts and supple gracefulness, her long alb coming down to her ankles. She sits on the tripod, her bare feet dangling off the floor, her body slumped, not quite herself, thoughtful, her eyes gazing down, looking into a small dish, presumably filled with water from a sacred spring, perhaps fragrant with a sweet aroma. In her right hand she holds a sprig of laurel, Apollo’s holy plant. The ceiling of her oracular chamber is low, and beneath her feet, below the floor, the artist has depicted a void.”

William J. Broad

Who was the Pythia? Contrary to what a twentieth-century scientific consensus claimed, she was neither a dupe nor a tool in the hands of savvy priests. She was not a junkie babbling under the influence of subterranean gas, either. Nor was she possessed by the devil who was violating her disguised as Apollo, as believed early Christians. Those outrageous modern claims have nothing in common with what respectable ancient sources and greatest intellectual authorities stated about her. For them, she embodied the holiest of all mysteries: of the possibility of human connection and communication with the divine. She was revered by the greatest minds of her times. Granted, ancient Greece was to all intents and purposes a misogynistic culture. Broad writes:

“Such regard was extraordinary for anyone, much less a woman. Most of ancient Greece lived by a code of extreme male chauvinism, at times of misogyny. Philosophers taught that men were superior to women even as artists such as Euripides railed against the oppression of females. For the middle and upper classes of Athens, a woman’s place tended to be in the home, working as a mother and a domestic manager, rarely allowed out except during festivals. Female babies were often victims of infanticide because of the economic drain of dowries. Men ruled public life. Some temples banned women and pigs. Some gods, such as Heracles Misogynous, sang the virtues of hating women. Even in the sacred environs of Delphi, woman petitioners seldom if ever had the authority to question the Oracle directly but instead had to put their questions through male intermediaries. Yet the jarring contradiction—suitable for any number of psychoanalytic studies—is that the greatest authority of ancient Greece was a woman.”

More precisely, there were numerous Pythias, one succeeding the other. They were members of mystical sisterhood, a sorority carefully guiding their sacred secrets. They enjoyed high social standing and freedom, unlike other Greek women. Men working at the sanctuary knew little of their comings and goings. One of the Pythias named Clea was close friends with Plutarch, himself a high priest of Apollo. He held her wisdom in extremely high esteem and had a lot of respect for her secrets.

In winter months, the oracle grounds were taken over by ecstatic worshipers of Dionysus. It seems that Clea was a member of that cult as well. Plutarch did not reveal her secrets, but just wrote instead: “Let us leave undisturbed what may not be told.” Dionysus was an inherent part of the Delphic mystery. The east side of the temple was dedicated to Apollo, but its west side was sacred to Dionysus – the god of wine and animal impulse, the loosener of civilized bonds. His side of the temple faced the setting sun and connected to Night and eerie orgiastic cults of the maenads. As Broad describes:

“In the chill night air, often under the stars, accompanied by torches and a beating drum, led by a double flute and a youth playing the role of Dionysus, the worshippers would dance their way up the cliffs behind the temple and climb seven miles to the Korykian cave, where their rites continued amid the large stalagmites that were easily seen in flickering light as divine phalli. Little is known of what occurred there because the rite was part of a mystery cult whose initiates pledged to keep their activities secret. It appears that the orgy could include sexual liberties in which the women might swiftly embrace their male companions, though scholars say the god did not demand such tribute. His rapturous devotees were free to act, or not, amid the surrender of the human spirit to the will of the god. The frenzied women were known as maenads, after the Greek verb meaning to be mad or furious.

Plutarch tells us that the rites culminated in screams and shouts and heads thrown back.”

![Apollo and Dionysus at Delphi, Attic vase, fourth century BC]()

Apollo and Dionysus at Delphi, Attic vase, fourth century BC

After the secret rites of winter brought about rebirth through a reconnection with the sacred chaos, the Oracle could proceed with its sheer blinding brilliance and keep delivering its uncannily accurate predictions in the months when the sun was at the height of its power. The messages of the Oracle were lofty but never arrogant. She always acknowledged the limits of knowledge. She protected the sanctity of life, regardless of the person’s social position. Notably, she used her power to free thousands of slaves. And she had little patience for arrogant wealthy supplicants.

![Orestes at Delphi, via Wikipedia]()

Orestes at Delphi, via Wikipedia

The greatest minds of the time – Socrates, Aristotle and Plato – were closely connected with Delphi. In a famous prophecy, the Pythia professed that no man was wiser than Socrates. Humbled, the great philosopher spent his life searching for the meaning of this prophesy. In Broad’s words: “Even as his constant questioning made him poor and unpopular, religious duty kept him asking and searching, trying to understand the Oracle’s meaning. In the end, he decided it meant that real wisdom is the exclusive property of the gods and Apollo’s reference to him was ‘as if he would say to us, the wisest of you men is he who has realized, like Socrates, that in respect of wisdom he is really worthless.’” I know that I know nothing, as per the Socratic paradox. When another great man of his times, Cicero asked the Oracle what he should do to attain the highest fame, she responded that “he should make his own nature, not the opinion of others, his guide in life.” He became a master orator.

In the fourth century, the oracle ceased to operate. The site was pillaged, its ruins buried under a village now called Kastri. Nobody remembered the glorious past until in 1463 Cyriac of Ancona, a Renaissance scholar, climbed the Parnassus and realized with astonishment what he was looking at. William Broad’s extraordinary book narrates the history of rediscovery of Delphi, most notably the scientific discomfort with the mystical aura surrounding the place until this day. First, the hypotheses of subterranean gases was vehemently rejected on the grounds that the Oracle was nothing but a fraud. When it turned out that there were in fact gases emitted into the sacred chamber, a new theory emerged, according to which the Pythia was high, and her babbling incoherent mutterings had to be made worthy of the gods by the male priests. Wisdom and inspiration of the Pythia accompanied by her obvious psychic abilities was not something readily accepted by science. She will remain elusive and unknown. “The wisps of ethylene and bouts of rapturous intoxication” do not prove that what happened in Delphi was a purely physical process. As the scientist Jelle Zeilinga de Boer, the scientist chiefly responsible for the discovery of the Delphi subterranean gases, remarked in an interview with William Broad:

“… the chemical stimulus in no way explained the Oracle’s cultural and religious power, her role as a font of knowledge, her liberation of hundreds of slaves, her encouragement of personal morality, her influence in helping the Greeks invent themselves, or—by extension—whether she really had psychic powers. Even if her prognostications were judged to have no basis in literal foreknowledge, it gave no explanation for how she reflected the underlying currents of ancient Greek society and how her utterances stood for ages as monuments of wisdom. It said nothing of how the priestess inspired Socrates or functioned as a social mirror, revealing the subconscious fears and hopes of those who sought her guidance, or of how she often worked as a catalyst, letting kings and commoners act on their dreams. In futility, the situation was like attributing masterworks of twentieth-century literature to the fact that major authors indulged in heavy drinking.”

The Pythia eludes all attempts to demystify her. A Victorian painter John Collier captured her spirit wonderfully in his painting done in 1891. In this wonderful canvas, her eyes are closed, her concentration deep, “as if her mind was moving through all time and space” (Broad’s description). Will we ever fathom her divine ecstasy?

![Giorgio de Chirico,]()

Giorgio de Chirico, “The Enigma of the Oracle”

Sites with photos of Delphi:

http://www.discovergreece.com/en/mainland/central-greece/delphi

http://ancient-greece.org/history/delphi.html

http://ancient-greece.org/archaeology/delphi-archaeology.html

Sources:

William J. Broad, The Oracle: Ancient Delphi and the Science Behind Its Lost Secrets, Kindle edition

Fritz Graf, Apollo (Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World), Kindle edition

Roger Sworder, Science and Religion in Archaic Greece: Homer on Immortality and Parmenides at Delphi, Kindle edition

Related posts:

http://symbolreader.net/2015/08/23/to-apollo-the-averter-of-evil-the-bringer-of-harmony-part-1/

http://thetarotnook.com/2013/09/06/the-fascinating-flickering-tongue-of-the-pythia/

![]()

![]()